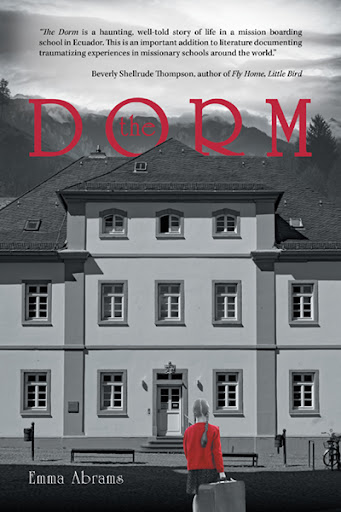

New From Emma Abrams

The Dorm

A classic story of abandonment and survival. A work of fiction based on the author’s real life experiences growing up in South America.

“The Dorm is a haunting well-told story of life in a mission boarding school in Ecuador. This is an important addition to literature documenting traumatizing experiences in missionary schools around the world.”

— Beverly Shellrude Thompson, author of Fly Home, Little Bird

Books

The Dorm

Andie Parker has just been told that she may have unconsciously taken on someone else’s identity as a child. But how could this be? How could she not know who she is?

The police have found a body of a little girl in the basement of a missionary boarding school; a little girl they believe to be Andie Parker. But the woman living as Andie Parker knows this must be impossible. The little girl had to be her dormmate, Miriam, who went missing at the age of seven. And yet, the police and even her own family aren’t quite convinced she is who she says she is.

Available on Amazon, Nook Store, Apple Books, Google Play, Friesenpress and Kobo Store

About

Emma Abrams is a West coast girl, living almost all her life within a day’s drive of the Pacific Ocean, albeit on two different continents. As a daughter of missionaries, Emma is keenly aware of the pros and cons of the Third Culture Kid world, which she explores in her writing. Much has been written about TCK’s, but learning to live in the “Muggle world” has been a lifelong quest. An avid reader, books were her escape hatch as a child, and anything from Nancy Drew to Encyclopedia Brittanica was on her radar. The strong literary characters she adored helped her navigate re-entry to living in North America, and nudge her own characters to deeper waters of self-awareness and integrity. See Bio

An excerpt from The Dorm…

I curled my body as small as I could. We had been woken up and ordered to a room at the end of the hall. The two beds were filled with Big Girls and we Little Girls were told to sit on the rugs on the floor. Two candles lit the whole room, casting eerie shadows and making faces gruesome. I only remember clearly how scared I was, looking up at the faces of the Big Girls, two of them on the chairs, and one sitting cross-legged on a desk, and the rest standing against the walls of the room. And Zippy, this was her room, was telling us a story, a story so scary that I covered my eyes with my hands. She was telling us that we were ‘the witnesses’: We had to remember so we could warn the next Little Girls who would come to live in the dorm.

I was at least twenty-five when I first heard the term ‘urban legend’. Also called ‘urban myth’, described in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “an often lurid story or anecdote that is based on hearsay and widely circulated as true”, it was not in our community vocabulary. But I was very familiar with the concept and I immediately thought back to the stories whispered under the cover of night about dorm kids being kidnapped out of their beds, or somehow disappearing. The Big Girls gathering us to warn us, to make us witnesses. And to a very vulnerable little girl, one thousand miles away from her parents, the fears these stories evoked never dissipated, but rather, distilled into a form of paranoia that still plagues the adult me.

I was six and suddenly thrust into a foreign place, The Dorm, with new faces and new rules. New everything. I knew that two older boys, both in high school, were from the same mission field as me, Peru, but they were very distant. A long way from a six-year-old’s small bubble. And the school in Quito was completely different from the little school in Lima where I started first grade. Well, a couple months of first grade. That is a different story.

The new rules in my new life were harder still, the punishment meted out for misbehavior graphically illustrated by the daily spanking of a boy named Mikey Silver. I was in the bathroom the day the dorm father broke the brush on Mikey’s behind, and I am haunted by this. It was the same brush the dorm mother used on my hair. Before she cut my identifying waist-length tresses to the chin-length bob as seen in my school photos.

Bells ruled our lives from the wake-up buzz, to the last bell of the day, the one that called us all downstairs for evening devotions. Each meal had two bells, the first being the warning bell. Of course, the school had bells morning, noon and afternoon: Warning, starting and dismissal. Some teachers had little bells on their desks to prepare the class for changing subjects, or to get our attention. And since we lived right on the school campus, it took no time at all to let the bells dictate the time of our lives.

It was only on the weekends that we got a break from the school schedule. (Yes, we still had the bells for meals and for devotions, and the buzzer sounded when it was time to leave for the two Sunday church services.) We had hours to ourselves to fill as we cleaned our rooms, did our chores and played. And of course we had time to remember the beloved people we were no longer with. We played hard and talked non-stop to fill those hours.

But it was the nights that were the hardest, when our bodies were too tired to go on, but our minds still able to produce painful memories. Every sassy comment to our parents, every naughty deed, every fight or slammed door was replayed while our pillows soaked up our silent tears. Homesickness was not just a term. It was a terminal disease.

In the night, the whispered stories of the older girls would sometimes distract us, horror of the unknown and barely possible preferable over the horror which was our reality. But sometimes those tales would conjure up nightmares, very real nightmares. When my very real nightmare began, I think it got lumped into the greater nightmare my life had turned into, the non-stop, never-ending and unbearable separation from my parents. It all was part of the whole.